From "Submitted" to "Certified"

An Interview with Our Head Grader at Metanet Academy

What actually happens when you click “Submit” on a Metanet Academy lab?

In many online courses, grading is an automated afterthought—a script checks your syntax, gives you a checkmark, and you move on. But at the Metanet Academy, we take a different approach. We believe that true mastery of the BSV blockchain requires more than just getting code to run; it requires a fundamental shift in how you think about data, trust, and architecture.

We sat down with the person responsible for grading students and upholding the Academy’s standards. In this deep-dive interview, we explore the philosophy behind our assessment model, the specific “evidence-based” habits that separate top-tier students from the rest, and why we prioritize debugging skills over rote memorization.

Role and Philosophy

How do you describe your role in the Metanet Academy, and how has it evolved?

I like to think of myself as a mentor to each student. I want to see people succeed and get the most out of the course, especially when they hit the first “real” friction points and are tempted to give up.

More formally, I’m responsible for assessment integrity and day-to-day academic support. This includes setting the bar, grading written answers and lab submissions, responding to student questions and course feedback, and resolving the occasional ambiguity or misunderstanding in a question. Early on, the role was mainly grading plus basic support. Over time, it has evolved into quality control for the entire learning experience. I look for recurring patterns in where students get stuck or misinterpret something in the module text or lab write-ups, then feed that back into improvements. If the fix is small and uncontroversial, I update the module text immediately; if it requires a wider change, I track it for the next iteration so we’re not patching around the same confusion repeatedly.

In practice, that leads to two consistent Academy habits. First, I push students toward evidence-based debugging rather than guesswork, because most lab blockers are environment and integration issues (ports, Docker, LARS services, wallet state) rather than deep blockchain errors. Second, I keep grading fair and predictable by aligning feedback to the exact wording and intent of the lab, while also improving the material so future students don’t hit the same avoidable traps.

What principles guide your approach to evaluating student work?

My evaluation is purely evidence-based. I grade what is demonstrated in the submission against what the module question or lab requirement actually asked for, not what I personally think the student should have answered or built. I prioritise correctness first, clear reasoning second, and alignment with Metanet/BSV best practice third. I also focus on whether the student has grasped the key concept or intent of the module or lab, rather than judging the submission by its length.

I keep feedback action-oriented by explaining what to change, why it matters, and how to verify the fix or confirm the behaviour. AI is used to help ensure submissions are marked objectively and fairly against the approved standard, using the Academy’s model answers as the reference point.

What does “mastery” of BSV concepts look like at different stages of the program?

In the early stage, mastery means students can explain the core terms accurately—UTXO, SPV, wallets, signatures, txid, TPN, encryption, and related fundamentals—and can describe basic blockchain workflows without guessing or hand-waving. They don’t need to be advanced, but they do need to be precise and consistent with the Academy’s terminology and trust model.

In the mid stage, mastery shows up as practical competence. Students can complete the lab TODOs, explain why the code produces the resulting behaviour, and debug effectively when something breaks. At this point, the key signal is that they can move from symptoms to causes in a disciplined way, especially once they’re given the right hints about where to look.

In the later stage, especially in an individual project, mastery looks like the ability to design and justify real application flows using BRC-100 and other relevant BRCs. Students should be able to explain trade-offs, defend design decisions, and align their architecture with how BSV apps are built in practice, including wallet standards, authenticated flows, and auditability.

Rubrics and Standards

Do you use standardized rubrics across courses, or course-specific rubrics? What core criteria never change?

I use course-specific rubrics, because each module and lab is testing a different set of outcomes. However, the core criteria never change. A submission must answer the question that was actually asked and demonstrate understanding of the key concepts. It must be technically correct, the reasoning must be coherent, and the work must follow the blockchain architecture and trust model that the course teaches.

How do you balance correctness, clarity, and real-world applicability in grading?

I treat correctness as the non-negotiable baseline: if an answer is wrong, clarity can’t rescue it. Once it is correct, clarity is how I judge understanding, because students should be able to explain what they did and why. Real-world applicability comes third and only when it matches the intent of the question or lab. I’m not grading extra ideas or different architectures unless the module is explicitly asking for design trade-offs; the goal is alignment with the Academy’s trust model and the standards we teach, not improvisation.

How do you ensure consistency when multiple graders or TAs are involved?

We keep consistency by anchoring decisions to the exact wording of the module questions and the stated intent of the lab requirements. We then cross-check submissions against the Academy’s model answers and reference expectations, so marking stays aligned to an agreed standard rather than individual preference. Finally, we use subject-trained AI as an additional consistency layer to help validate that grading is objective and aligned with the approved standard.

A further practical step that helps, especially in labs, is to require reproducibility as part of the check. If the grader can run the student’s work end-to-end using the same steps and see the same behaviour, grading becomes much less subjective and much more consistent across different reviewers.

What’s your policy for partial credit on complex, multi-step tasks?

My default approach is that complex, multi-step tasks are assessed on whether the student achieved the intended outcome end-to-end and whether the core concept was implemented correctly. In practice, we rarely rely on formal partial credit because the Academy is structured to help students reach a correct working result rather than to award points for an incomplete state.

If a submission shows the right understanding but is blocked by an environment issue or a small integration mistake, I treat that as a solvable blocker. I give targeted guidance, ask for evidence such as logs or screenshots, and allow the student to correct and resubmit.

Where a submission is incomplete in a way that breaks the trust model or bypasses the intended architecture, it isn’t treated as partially correct, because the missing step is the point of the task. The goal is to get students to the correct mental model and a working implementation, not to reward a near-miss that would fail in a real BSV application.

Labs and Practical Assessments

What core competencies are you looking for in labs (e.g., SPV, UTXO handling, peer-to-peer workflows, standards like BRC-100)?

Metanet Academy labs are about practical competence, not just theory. I’m looking for evidence that a student can take the concepts from the module and apply them in a working system that behaves the way the lab intends, not a “looks right on paper” solution.

A core competency is correct UTXO usage. Students should demonstrate that they understand how state and value live in outputs, how spending consumes an output and creates new ones, and how that shapes application design. Closely related is a correct SPV mental model: what is trusted, what is proven, and what SPV does and does not guarantee. When students can explain inclusion proofs and trust boundaries without overclaiming, it’s a strong sign they understand the foundation.

I also look for wallet-mediated authorisation patterns. The labs are designed to reflect how real BSV apps work: user consent matters, identity matters, and certificates or authenticated flows matter where the module calls for them. If a student bypasses the wallet or hard-codes a “fake” path that avoids authorisation, they’ve missed the intent of the lab even if the UI appears to work.

Where a lab is teaching a specific standard such as BRC-100, I’m looking for correct use of that standard’s flow and terminology, not an alternative architecture that happens to function. The goal is alignment with the model the Academy is teaching so students build the correct instincts and can transfer that knowledge to real projects.

Finally, the lab has to run end-to-end and be verifiable. Students should be able to demonstrate the system working in practice using reproducible steps, and the behaviour should match the reference application’s intent as closely as possible. That end-to-end verification is what turns the lab from “code written” into “competence demonstrated.”

What common mistakes do you see in labs, and how do you coach students to correct them?

Most lab “mistakes” are not deep blockchain engineering failures. The most common issues are practical and environmental: students are still building confidence with their local setup, so they run into problems with ports already in use, Docker not running, LARS services failing to start, or a dev server quietly switching ports. We help them through those issues because they block progress, but the goal is always to get them back to the actual learning objective rather than turning the Academy into an IDE troubleshooting course.

Another recurring pattern is a mismatch in mindset. Many students arrive with habits from traditional web development where it is normal to rely on centralized services, indexers, or “just call an API.” In our labs, that mindspace often needs to be reshaped toward the constraints and strengths of the UTXO model, peer-to-peer workflows, and wallet-mediated authorisation. When a student tries to shortcut the architecture, the lab may still appear to work, but it no longer demonstrates what the module is teaching. Coaching here is about explaining the intent of the requirement and helping them align their approach with the Academy’s trust model.

Beyond those two themes, students generally do not make many major conceptual errors. Most issues are minor misunderstandings or simply not reading the requirement closely enough, such as answering a broad statement when the requirement is testing a specific piece of knowledge, or implementing something adjacent to the requirement rather than the requirement itself. In those cases the fix is usually straightforward: I point out the exact line in the specification they missed, explain what is really being tested, and ask them to make one small, targeted correction or provide a piece of evidence. A short nudge and a quick verification step is often enough to get them back on track without discouraging them.

Written Answers and Conceptual Understanding

What distinguishes an excellent written answer from a merely adequate one?

An adequate written answer is correct, but it tends to be generic. It often reads like a reasonable explanation you could give for many blockchains, rather than showing that the student has understood the specific model and terminology the Academy is teaching.

An excellent answer is still concise, but it is precise. It uses the Academy’s terms correctly and consistently, because those terms carry important meaning. For example, using “Transaction Processor” where the course uses that concept is better than defaulting to “miner,” because it signals the student is aligned with the model being taught rather than relying on inherited assumptions from other ecosystems. The same applies to terms like UTXO, SPV, Merkle proof, wallet authorisation, and identity: correctness is not just recognising the word, but using it accurately in context.

Excellent answers also demonstrate awareness of trust boundaries. The student makes it clear what is proven, what is assumed, and what is outside the scope of the proof. This is where many otherwise-correct answers become misleading, such as claiming “SPV proves everything,” or implying that a Merkle proof validates the full semantic correctness of a transaction rather than demonstrating inclusion. The best answers avoid overstating and make careful distinctions without becoming overly technical.

Finally, excellent answers usually include a concrete example, even if it is only one sentence. A small example forces precision and demonstrates real understanding, such as briefly describing how a wallet verifies a payment request, how a UTXO is spent to create a new output, or how an SPV proof confirms a transaction’s inclusion in a block header chain. They also avoid sweeping generalisations and stick to claims they can justify, which is the habit we want students to develop for both written module submissions and engineering work in the labs.

How do you assess a student’s grasp of the BSV trust model, regulatory compliance considerations, and the network’s stable protocol?

For the trust model, I look for whether the student can clearly articulate what should be trusted, what does not need to be trusted, and why. In particular, I want them to explain what SPV actually proves and what it does not. A strong answer identifies the boundary between cryptographic verification and assumptions about the wider world, and it avoids vague claims like “the blockchain guarantees everything.” Students demonstrate real understanding when they can describe who is verifying what, using which evidence, and what the result means in practical terms.

For regulatory and compliance considerations, I’m not looking for legal advice. I’m looking for maturity and a clear separation of concerns. Students should be able to distinguish protocol capabilities from business or legal policy, and they should avoid making absolute claims such as “this is compliant” or “this is legal everywhere.” A good answer acknowledges that compliance is context-dependent and typically sits at the application and organisational layer, while the protocol provides the technical properties that can support compliant designs.

For stable protocol, I look for whether the student understands the practical implications of stability. If the base protocol is stable, developers can build applications that rely on long-lived data formats and predictable behaviour over time. That supports long-term application design, durable on-chain records, and systems that do not need to be continuously rewritten to chase breaking changes. Students show mastery when they can connect protocol stability to real engineering outcomes, such as auditability, long-term interoperability, and confidence in building serious applications on top of the network.

How do you evaluate the student’s ability to explain SPV simply and accurately?

I look for a plain-language explanation that is accurate without being inflated. A strong answer explains that SPV verifies inclusion in the blockchain by checking block headers and using Merkle proofs to show that a transaction is included in a block, without requiring a full node to download and validate everything. The key is that the student describes what SPV proves, and just as importantly, what it does not prove.

I also watch for two common failure modes. One is overclaiming, such as implying SPV “downloads everything you need,” “proves everything,” or “means you don’t have to trust anything.” The other is the opposite extreme: overwhelming detail that obscures the point and makes the explanation harder to verify. Correct simplicity beats both generic hand-waving and unnecessary technical overload. If the student can communicate the trust boundary clearly in a few sentences, they’ve demonstrated real understanding.

What evidence do you look for that students understand the implications of the UTXO model on application design?

I look for evidence that the student thinks in terms of outputs as both value and state, and understands how that state moves forward. A strong answer describes state as “what is in the outputs,” then explains that spending consumes an existing output and creates new outputs, which is how applications evolve state over time. When students can describe that lifecycle clearly, it usually means they’ve internalised the core model rather than treating the blockchain like a generic database.

I also look for whether they can connect that model to real design consequences. Students show deeper understanding when they can explain why UTXOs affect concurrency and coordination, because two parties cannot spend the same output at the same time without conflict. They should also be able to explain ownership and control in practical terms: whoever can satisfy the locking conditions controls spending, and that shapes how applications model permissions. Finally, composability matters because UTXOs create clear, discrete units of state that can be consumed and combined in different ways, which influences how you design workflows, token patterns, and multi-step interactions. When a student can make these connections in clear language, it is strong evidence they understand the implications for real application design.

Integrity, Identity, and Authenticity

What methods do you use to ensure the work is the student’s own?

I look for consistency and traceability. A genuine submission usually fits the student’s prior level and style, and the student can explain what they built or wrote without relying on vague statements. Simple follow-up questions are often enough to confirm authorship, because someone who did the work can describe their design choices, point to the relevant part of the code, and explain what they would change if something broke.

I also rely heavily on reproducibility. If a student runs into problems, I expect them to describe the exact symptoms, provide evidence such as logs or screenshots, and explain how they would approach diagnosing the issue. The ability to reproduce behaviour and reason through a fix is a strong signal that the work is theirs, and it reinforces the Academy’s expectation that engineering is evidence-based rather than guesswork.

Finally, identity continuity matters at the program level. The final Academy certificate is awarded to the user identity key that has been used throughout the labs, which creates a consistent link between lab activity and the student’s authenticated participation over time.

Do you rely on cryptographic identity or certificate-based methods to verify authorship or participation? If so, how do those shape your grading workflow?

Yes, identity is part of how we keep participation and outcomes traceable without turning the process into something heavy-handed. When I’m interacting with students, especially when diagnosing lab issues, I often ask for screenshots of their Metanet client as used for the lab work. That helps confirm the student is operating in the expected environment and using the correct identity context, which becomes particularly important once labs involve authentication, wallets, and backend services.

This also ties into the program’s continuity requirement. As mentioned above, the final Academy certificate is awarded to the identity key the student has used throughout their labs. That creates a consistent link between a student’s authenticated participation over time and the work they submit, and it supports fair assessment when students need help troubleshooting or clarifying what they did.

How do you handle suspected collusion or use of unauthorized tools while maintaining a culture of trust and learning?

I treat it as a learning conversation first, not an accusation. If something looks inconsistent, I ask the student to explain the submission in their own words and then make a small change either live or in follow-up. Someone who genuinely understands their work can usually do that quickly. If they cannot explain basic design choices or make a simple targeted edit, that becomes evidence that the submission may not reflect their own understanding.

We also take a pragmatic stance on AI tools. We do not prohibit AI usage entirely, because it can be useful for troubleshooting or summarising, but we are clear that students remain responsible for correctness and comprehension. The student needs enough foundational understanding to recognise when AI advice is wrong, off-scope, or incompatible with the Academy’s trust model and architecture. In practice, that means AI can assist, but it cannot replace the student’s ability to reason about what the code is doing and why.

The overall goal is to protect all students and keep standards meaningful without creating a hostile environment. The focus is always on learning and demonstrated understanding, not policing for its own sake.

Feedback Loop and Continuous Improvement

You’ve been responsible for responding to feedback about the Academy—what themes come up most often?

Feedback typically centers on three key areas. The first is ambiguity in wording, especially in “fill in the blank” style questions where multiple answers can be plausibly correct. When that happens, we treat it as a content problem rather than a student problem. If a student can justify an alternative phrasing that matches the module’s intent, we expand the accepted answer variants so grading is not a guessing game.

The second theme is environment friction. The most common blockers are not conceptual blockchain issues but practical setup problems: ports already in use, Docker not running, LARS services failing to start, local wallet services producing noisy errors, or configuration mismatches that distract from the learning objective. A lot of our support work is about helping students isolate what is actually broken and, importantly, helping them recognise which errors are irrelevant so they don’t waste time chasing the wrong thing.

The third theme is the “why was this marked wrong if it’s also true?” discrepancy. This often comes down to the question testing a specific definition or concept, while the student answers with a broader statement that is technically true but does not demonstrate the intended learning outcome. When we see this repeatedly, we tighten question wording or add clarifying notes so students understand what is being tested.

Beyond those three, two other patterns show up regularly. Students often ask for clearer examples of what a “good” answer looks like in the Academy’s style, which reinforces the value of model answers and consistent terminology. And in labs, students frequently want reassurance on what is required versus what is optional, because they may be tempted to overbuild or add features that are outside scope. In response, we try to make the required behaviour and verification steps explicit so students can focus on correctness and learning rather than on guesswork.

Can you share a time when student feedback led to a concrete change in rubrics, assignments, or course structure?

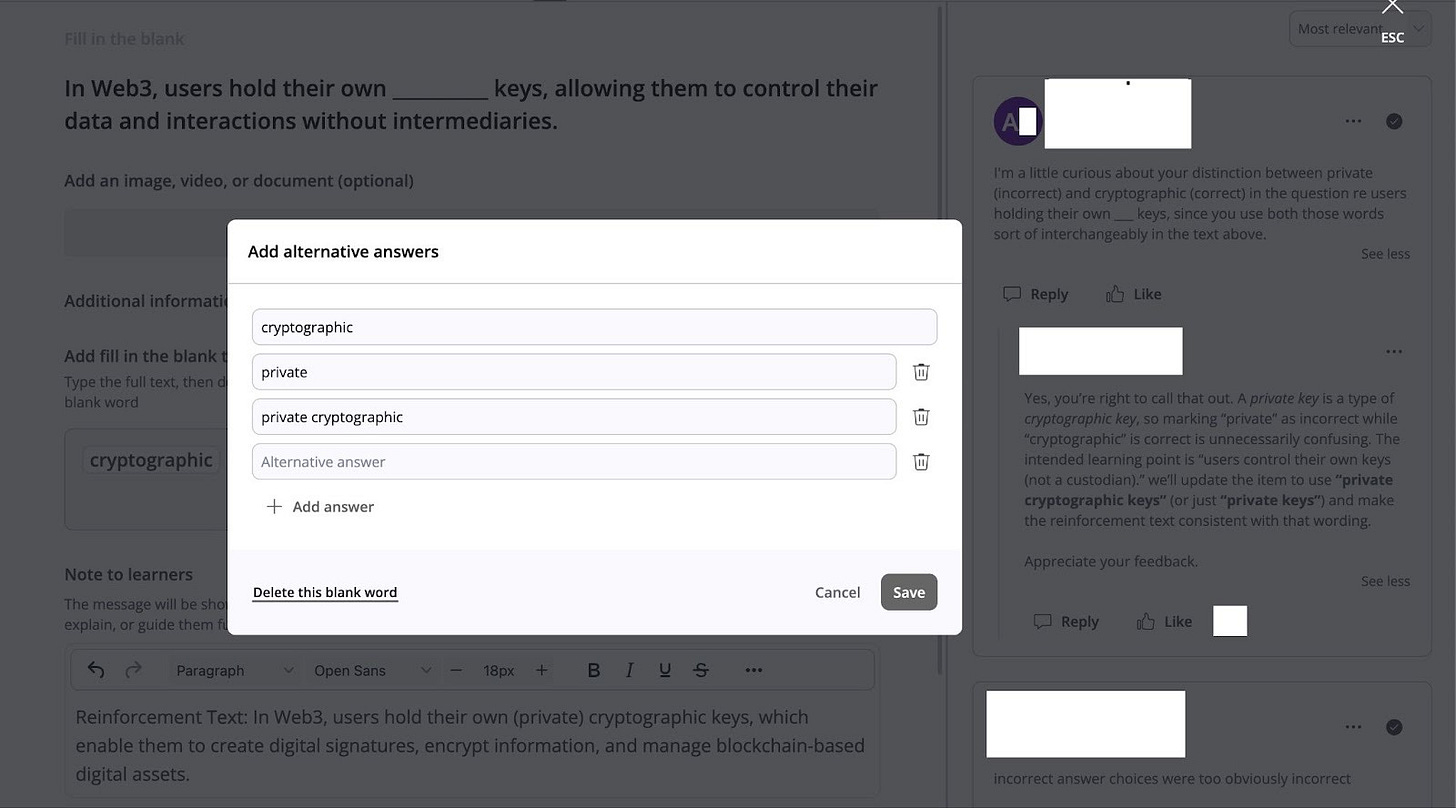

The screenshot shows a concrete example of how student feedback leads to an immediate content and grading update in the Academy.

It shows a fill-in-the-blank question that reads: “In Web3, users hold their own ______ keys, allowing them to control their data and interactions without intermediaries.” A student comment in the right-hand discussion highlights an ambiguity: the course text uses “private” and “cryptographic” in a way that makes both feel interchangeable, so marking one of them as “incorrect” is confusing.

In response, the question configuration is updated by opening an “Add alternative answers” dialog and adding additional accepted answers. The dialog shows “cryptographic,” “private,” and a combined option “private cryptographic,” with a Save button to apply the change.

This is a good example of student feedback producing a concrete change because it does not just explain the issue; it updates the assessment so grading better matches the intended learning point (self-custody and control of keys) and reduces avoidable disputes caused by wording ambiguity.

How do you prioritize which feedback to act on quickly versus track for future iterations?

I prioritise feedback based on whether it blocks a student from completing the course as intended. If something prevents progress or creates repeated, unnecessary failures, it becomes a quick fix. That includes broken setup steps, missing or incorrect instructions, port or environment issues that stop labs from running, and wording clarifications where students are reasonably interpreting a question in multiple ways. If the correction is small and clearly improves fairness or reduces friction, I prefer to apply it immediately rather than letting the same problem hit the next set of students.

By contrast, feedback is tracked for future iterations when it is valuable but not blocking. “Nice to have” improvements that would make the course smoother are important, but they do not justify constant mid-stream changes. Likewise, deeper reorganisations—such as restructuring a module, reordering concepts, or rewriting a lab narrative—need a full revision pass so we can preserve consistency across the curriculum and avoid introducing new confusion. In those cases, tracking the feedback and addressing it in a planned iteration produces a better outcome than patching the material ad hoc.

What’s your turnaround time target for feedback, and how do you keep it predictable?

My target is simple: fast enough that students do not stall. In practice, I respond quickly to blockers and aim to keep a consistent grading cadence so students have a reliable sense of when they will hear back. Predictability comes from using a stable rubric and reusing structured feedback templates for common issues, which keeps both the standard and the tone consistent across many submissions.

It is also important to note that feedback is not time-critical in the strict sense. Students can usually move on to the next question or lab without waiting, although timely feedback is still valuable because it helps correct misunderstandings early. For written submissions, I generally aim to respond within one to two days depending on workload. I review submissions in chronological order for fairness and consistency, but if a student is blocked by a critical lab issue, I will intervene immediately to get them back on track and prevent wasted effort.

Fairness and Accessibility

How do you accommodate diverse backgrounds—students strong in code but new to BSV (or vice versa)?

I accommodate diverse backgrounds by separating coding execution from conceptual correctness. A student can write clean, professional code and still lose marks if they violate the trust model or bypass the architecture the Academy is teaching. Equally, a student with weaker coding skills can still earn credit if their reasoning is correct and their partial implementation demonstrates that they understand the core concept the lab is testing.

The labs are designed with that in mind. Students who are newer to development may take longer because they need more time with setup, debugging, and the workflow of building an app end-to-end, but they should still be able to complete the lab if they approach it methodically and follow the reference patterns. At the same time, students who are strong developers but new to BSV are supported in shifting their mindset toward UTXO-based design, SPV trust boundaries, and wallet-mediated authorisation, which are often the biggest conceptual transitions.

What steps do you take to remove ambiguity from prompts and grading criteria?

When you say “prompts” in this context, I interpret that as the questions students are expected to answer and the instructions attached to labs. When ambiguity shows up, we fix it at the source rather than forcing students to guess what the grader intended.

In practice, that means tightening the wording of the question so it tests one specific concept clearly, expanding accepted answer variants when multiple phrasings are reasonably correct, and adding short rubric notes that make the intent explicit—for example, “we’re testing X here, not Y.” The goal is that students can focus on understanding the material and demonstrating competence, not on decoding hidden expectations.

How do you manage regrade requests and ensure fairness without inflating grades?

I treat regrades as an alignment check, not a negotiation. The question is whether the student’s answer matches the module’s stated intent and the accepted standard, not whether they can argue for marks. If their answer genuinely satisfies what the question is testing, it should be accepted.

Where regrade requests reveal that multiple answers are plausibly correct, the right response is to fix the assessment going forward. That usually means tightening the wording or expanding the accepted answer variants so future students are not penalised for reasonable interpretations. The key principle is consistency: we do not move the goalposts on a per-student basis, but we do improve the material when a valid dispute exposes ambiguity.

Real-world Alignment

How do you ensure assessments reflect real BSV practices like SPV-first design, peer-to-peer networking, and vendor-neutral standards such as BRC-100?

We ensure assessments reflect real BSV practice primarily through the lab design itself. The labs are scaffolded with reference structure and targeted TODOs that deliberately channel students into the correct patterns, so they learn the intended trust model by building it. That includes UTXO-first state handling, wallet-mediated authorisation and identity, and standards-based flows such as BRC-100 where the module is explicitly teaching them.

Because the path is guided, the grading focus is less about evaluating arbitrary architectural choices and more about confirming the student completed the intended steps correctly, achieved the expected end-to-end behaviour, and can explain the trust boundaries and reasoning behind what they implemented.

Metrics and Outcomes

What metrics do you track to gauge student progress and the effectiveness of assessments?

Operationally, the LMS does a lot of the baseline tracking for us, including storing and recording whether students answered straightforward module questions correctly. On top of that, I pay attention to pass and completion outcomes for modules and lab submissions. So far we have not had failures when students submit coherent work, because my approach is to help them identify what is wrong, explain why it matters, and guide them toward a correct fix rather than letting them stall or quietly fail.

I also track where students tend to stall, because that is one of the strongest signals of what needs improvement. The stall points usually fall into three buckets: setup issues, conceptual misunderstandings, or code and integration problems. Alongside that, I watch the most common support questions that come up repeatedly. Those patterns are invaluable because they show where the course material needs tightening, where a lab instruction is ambiguous, or where we should add a short clarification so students can progress without unnecessary friction.

Where do students most commonly struggle, and how have you adapted to address those pain points?

Students most commonly struggle at the transition from simple, self-contained tasks into labs that involve running multiple services and integrating a backend. The conceptual material is usually not the hard part; the friction tends to come from the practical reality of development environments. Typical pain points include ports already in use, Docker not running, LARS services failing to start cleanly, dev servers switching ports unexpectedly, and wallet-related errors that look serious but are actually irrelevant to the lab’s learning objective. When students hit these issues, they can lose time and confidence because they do not yet know which errors matter and which ones are noise.

I have adapted by coaching students into an evidence-based debugging habit and by tightening the material where it repeatedly causes confusion. On the support side, I push students to verify the environment first, isolate one component at a time, and use simple logging to confirm what is actually happening rather than guessing. On the content side, when we see the same stall point across multiple students, we update the lab instructions, add clarifying notes, or expand accepted answer variants so the course becomes smoother for the next cohort. The goal is not just to help a single student through a blocker, but to remove avoidable friction from the path so students spend their effort learning the intended BSV concepts and workflows.

What does a successful graduate portfolio look like from your perspective?

A successful graduate portfolio shows consistent correctness across the whole programme. That includes a high percentage of correctly answered module questions, written submissions that clearly demonstrate understanding of the key concepts, and labs that are completed successfully end-to-end. At the final stage, it also includes an individual project that earns strong marks because it is coherent, aligned with the taught architecture, and demonstrably works.

For me, the defining features are not depth for its own sake, but correctness and clarity paired with a professional approach. A strong graduate can explain what they built and why, use the Academy’s terminology accurately, respect the trust model and wallet-mediated flows, and debug methodically when something breaks. That combination is what turns course completion into real readiness to build on BSV.

Operations and Tooling

What tools or automation (test harnesses, transaction simulators, verification scripts) are essential to your grading workflow?

The essential tools are the ones that make verification objective and repeatable. The starting point is consistency of inputs: students are given the same course material, the same lab requirements, and the same expected behaviours, so grading is not dependent on hidden assumptions. Where appropriate, we provide reference applications in private repositories so students can compare their implementation and so graders can verify what “correct” looks like in practice.

I also rely on AI review of student submissions as a consistency layer, especially for written answers where phrasing can vary while meaning stays the same. Used properly, it helps ensure marking is aligned with the approved model answers and reduces subjective drift across different graders or across time.

Beyond those, the most important “tool” in practice is reproducibility. The ability to run a student’s lab end-to-end, observe the behaviour, and confirm it matches the intended outcome is what keeps grading grounded in evidence. When students provide logs, screenshots, or a clear set of reproduction steps, it makes assessment faster, fairer, and easier to verify without guesswork.

How do you document grading decisions to maintain consistency and provide transparent feedback?

I document grading decisions in a way that makes them traceable, consistent, and useful to the student. The LMS provides the baseline record: it stores module results, captures written submissions, and preserves my feedback and follow-up messages in the same place the student sees the outcome. That creates a transparent audit trail of what was submitted, what was expected, and why a given response was accepted or rejected.

In my feedback, I keep the reasoning anchored to the module’s wording and the accepted standard rather than personal judgement. When a student is wrong or off-scope, I explain the specific point that was being tested, what was missing or incorrect, and what change would make the answer meet the requirement. For labs, I treat reproducibility as part of documentation: if a fix is needed, I ask for concrete evidence such as logs, screenshots, or reproduction steps, and I reference those directly when explaining what happened and how the student can verify the correction.

When a grading decision exposes ambiguity in the material, the documentation becomes part of the improvement loop. We record the reasoning, then update the prompt wording or accepted answer variants so the standard remains consistent for future students and the same dispute does not repeat.

Future Direction and Vision

If you could add or overhaul one component of the assessment model, what would it be and why?

If I could overhaul one component of the assessment model, it would be the LMS experience itself—both the student-facing flow and the admin tooling—because it is the main constraint on how smoothly the course can run at scale.

On the student side, the current LMS feels restrictive in terms of layouts and presentation. That matters because assessment is not just “content,” it is also how clearly the question, context, and expected standard are communicated. With more flexible layouts, we could present model answers, clarifications, and verification steps more cleanly, which would reduce avoidable ambiguity and help students move through the course with less friction.

On the admin side, the tools are functional but basic once enrolment grows. More robust controls for managing cohorts, tracking patterns in where students stall, and applying updates to accepted answer variants or rubric notes at scale would make the feedback loop faster and more systematic. The outcome would be the same standard of assessment, but delivered in a smoother way for students and with better operational support for the Academy as participation increases.

What advice would you give new students to succeed in both the labs and written assessments?

For written assessments, answer the exact question in your own words and stick closely to the terminology used in the module text. Precision matters more than length. If a question is testing a specific definition, make that definition explicit, avoid broad generalisations, and do not overclaim. A short answer that is correct and aligned with the Academy’s terms will score better than a long answer that drifts into generic blockchain language.

For labs, treat evidence-based debugging as part of the skill you are learning. Follow the TODOs carefully, make small changes in isolation, and verify each step before moving on. Most lab blockers are environment or integration issues rather than deep blockchain problems, so check the basics first: what is running, which ports are in use, whether Docker and LARS services are actually up, and what the logs say. Add minimal logging at the boundary points so you can see what is happening rather than guessing. If you can reproduce the behaviour, explain it clearly, and show how you verified the fix, you will progress quickly and learn the right habits for building real BSV applications.

Follow-ups and Scenario Prompts

Walk through a recent lab where the median submission missed the mark—what happened and how did you respond?

A good example is Lab L-9, which is the first point in the programme where students have to integrate a backend authentication service with the LARS development environment and local containers. The median “miss” is not usually a misunderstanding of the blockchain concepts. It is that students hit real integration friction and interpret it as a coding failure, then start changing the wrong things. The most common pattern is that their environment is not in the expected state—Docker is not running, ports are already allocated by previous services, or the lab’s dev servers switch ports and the student follows the wrong URL. At that stage, students can also be distracted by wallet-related messages that look alarming but are not actually the blocker for getting the lab working.

My response is to keep the assessment evidence-based while coaching them toward disciplined debugging. I ask them to show concrete evidence first—what command they ran, the first error in the logs, and what is actually listening on the relevant ports—before changing any code. We then isolate the problem by verifying one dependency at a time: confirm Docker is reachable, confirm the containers can start, confirm the backend process is running, confirm the frontend is serving on the correct port, and only then look at application logic. In most cases, once the environment is corrected, their code works with minimal or no changes. This approach preserves the integrity of the lab outcome while teaching the habit that matters most at this stage: diagnose with evidence, fix the real blocker, and verify end-to-end behaviour against the expected flow.

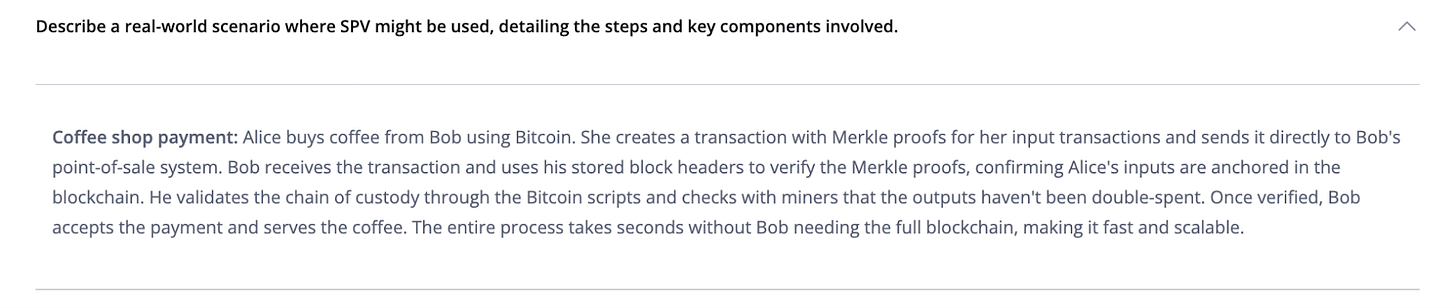

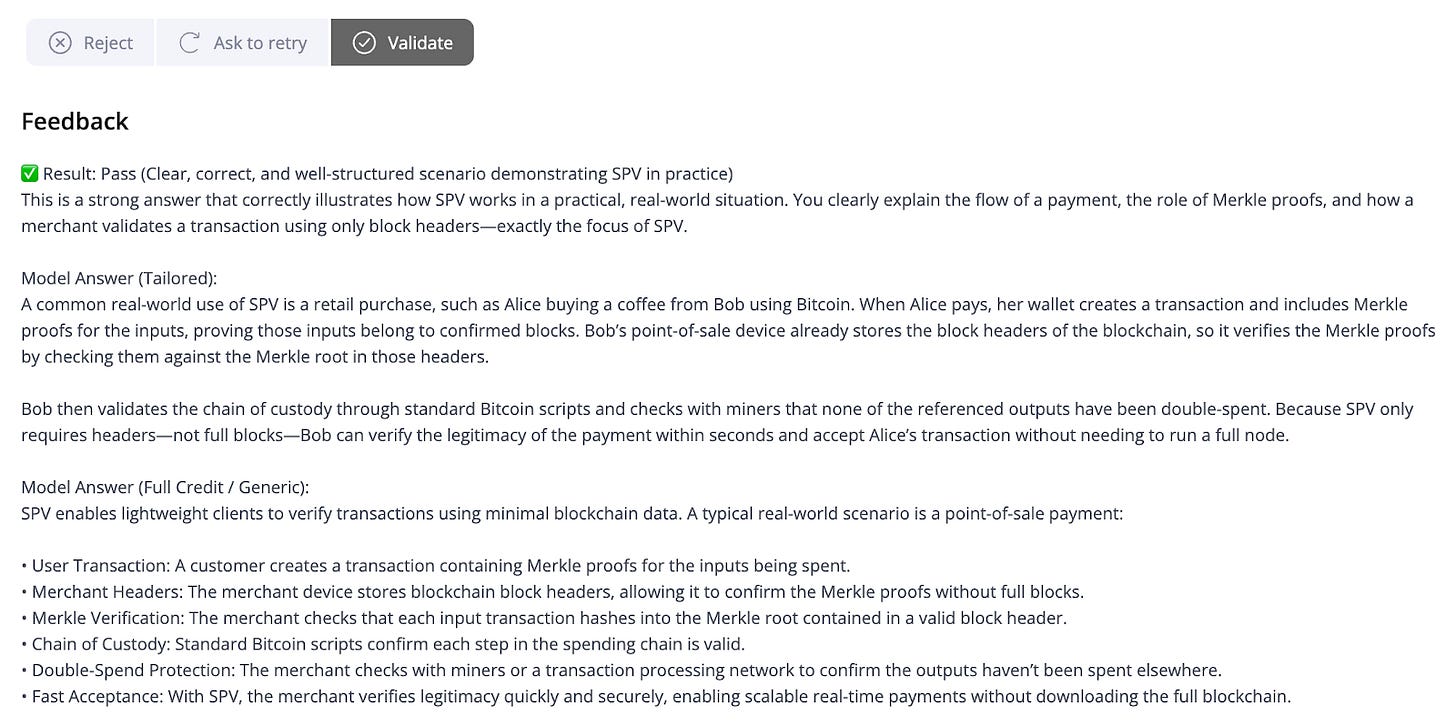

Describe a model written answer that clearly demonstrates deep understanding of SPV and peer-to-peer assumptions.

A strong SPV explanation makes two things clear: what is proven, and what is assumed. In SPV, a lightweight client verifies that a transaction is anchored in the blockchain by checking a Merkle proof against the Merkle root in a valid block header on the most-work chain. This shows inclusion without downloading full blocks, which is why SPV enables fast, scalable verification at the edge.

The peer-to-peer assumptions are equally important. SPV does not mean “no trust” or “prove everything.” The security model depends on honest majority proof-of-work and normal network propagation. For confirmed transactions, inclusion in the best chain provides increasing confidence as more proof-of-work accumulates. For unconfirmed transactions, confidence comes from peer-to-peer broadcast and monitoring for conflicts, combined with an acceptance policy appropriate to the risk.

The coffee-shop example submitted by this student fulfills these points explicitly by showing the Merkle-proof-and-headers verification that SPV provides, while also acknowledging the peer-to-peer assumptions involved in safe payment acceptance.

Conclusion

As our conversation highlights, the Metanet Academy certificate is not a participation trophy; it is a proof of work.

The rigor described within isn’t there to act as a gatekeeper; it is there to ensure that when you graduate, you possess the practical, evidence-based skills required to build real applications on BSV. From understanding the nuance of SPV trust boundaries to mastering the discipline of end-to-end debugging, the goal is to transform “web developers” into true blockchain engineers.

If you are ready to challenge yourself and build a portfolio that demonstrates real-world competence, we are ready to help you get there.

Join us at MetanetAcademy.com